One step closer to a rupture: Europe, the US and Turkey

Turkey’s relations with the EU and US are in freefall after its new offensive in northern Syria. The EU should do what it can to avoid a broader rupture between Ankara and the West.

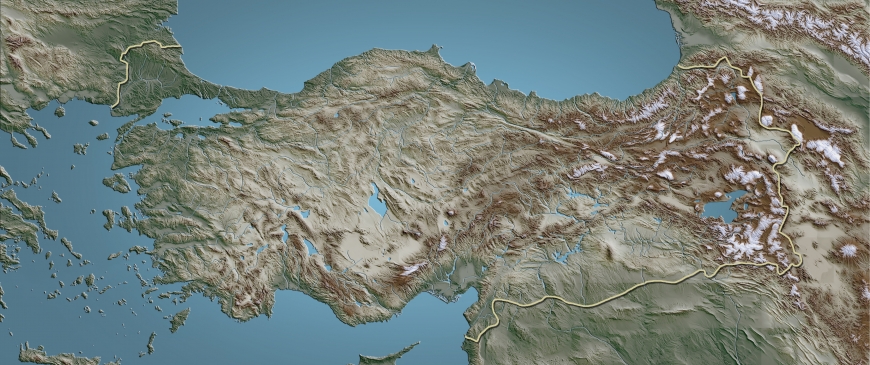

Turkey’s offensive against the Kurdish YPG in northern Syria has left relations with its Western partners in tatters. After encouraging Turkey to embark upon the operation by withdrawing US troops from the Turkish-Syrian border, US President Donald Trump has now imposed sanctions on Turkey, and threatened to “totally destroy and obliterate” its economy unless it desists from the operation. The EU has also condemned Turkey’s offensive, saying it “seriously undermines the stability and the security of the whole region”, and member-states have pledged to restrict arms sales to Ankara, while stopping short of a full embargo. Turkey’s image in the West has suffered tremendous damage: there is a lot of sympathy for the YPG, which helped defeat the Islamic State. Meanwhile, few are willing to take seriously Ankara’s argument that the YPG presence on its border represents a threat because of the group’s links to the PKK, a terrorist group that has been waging an armed insurgency in Turkey since the 1980s.

Turkey’s offensive against the Kurdish YPG in northern Syria has left relations with its Western partners in tatters

The EU’s move to suspend arms exports is unlikely to stop the Turkish offensive, given that Turkey views its operation as vital to national security. Instead, now that the Kurds have aligned themselves with the Syrian government and Russia to counter Turkey, fighting will probably end when Turkey and Russia come to an agreement. But Europe will pay the price for Trump’s rash move to suddenly withdraw US forces from the Syria-Turkey border. In the immediate term, there is a risk that renewed conflict will lead to a humanitarian crisis, and fighting has already allowed some IS members detained by Kurdish forces to escape. Turkey’s intervention could also put the 2016 EU-Turkey migration deal at risk if Ankara follows through with its plans to resettle some of the Syrian refugees it is hosting in the ‘safe zone’ it wants to set up in northern Syria. This would undermine the deal, as sending migrants back to Turkey would be contrary to the EU’s legal obligations if there were a risk of them being returned to Syria against their will. Finally, Trump’s withdrawal of US forces has undermined US credibility as an ally, and strengthened Russia’s position in the region. This in turn will reduce the EU’s influence, as member-states find it difficult to act in the region without the US.

More broadly, Trump’s erratic decisions, first appearing to condone Turkey’s operation, and then imposing sanctions in response to it, may lead to a rupture in US-Turkey relations, which would be profoundly damaging for the EU. Even if Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Trump manage to strike an agreement on Syria, this would not make the numerous other issues between Turkey and the US disappear. Relations between Ankara and Washington were deeply damaged by the American strategy of fighting the Islamic State in Syria, which was based on supporting the YPG. This support infuriated Ankara, leading it to shift its strategy in Syria and begin extensive co-operation with Russia. Moreover, most Turks think the US was too slow to condemn the attempted Turkish coup in 2016, and are convinced that Washington would not have minded had the plotters succeeded. Meanwhile, Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 surface-to-air missile system from Russia has been a major bone of contention with the US, and the clearest symbol of Ankara’s pivot to Moscow. Washington has suspended Turkey from participation in the F-35 fighter jet programme, arguing that the S-400 system is incompatible with NATO hardware and that the presence of a Russian radar system in Turkey would allow Moscow to capture intelligence about the new F-35 aircraft. The recent indictment by New York prosecutors against Turkey’s state owned Halkbank, accused of violating US sanctions on Iran, will also raise tensions.

Trump’s erratic decisions, first appearing to condone Turkey’s operation, and then imposing sanctions in response to it, may lead to a rupture in US-Turkey relations, which would be profoundly damaging for the EU.

Many in Washington no longer see Turkey as a real ally. In response to the deteriorating ties with Ankara, Congress has looked to increase co-operation with other partners in the region, in particular pushing for the US to align with Cyprus, Israel and Egypt in exploiting gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean. Congress will push Trump to take a tougher stance towards Turkey. Even if Trump and Erdoğan strike a deal on Syria, the S-400 will remain a source of friction. The 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) requires the US president to impose sanctions ranging from mild to severe on countries that purchase Russian equipment. Trump has delayed imposing these penalties, but he will not be able to do so forever. There is a strong bipartisan consensus on enforcing CAATSA, not only to send a signal to Turkey but also to reduce the risk that other US allies acquire Russian weapons systems.

Tensions between Washington and Ankara have created a poisonous and confrontational atmosphere that could disrupt NATO from within, putting European security at risk. The EU’s own moves to sanction Turkey are likely to further exacerbate tensions and fuel Turkey’s realignment towards Russia. Turkey will argue that the EU is hypocritically singling it out, and that many member-states are still selling weapons to Saudi Arabia despite its long and brutal war in Yemen. Western sanctions are likely to strengthen anti-Western sentiment in Turkey. And if Turkey is no longer able to buy European or American kit, it will turn to Russian equipment that is unlikely to be fully compatible with NATO standards. Turkey’s alignment with Russia would create problems for the EU, undermining its foreign policy across the Balkans and the Middle East. It could also diminish NATO’s reach and ability to operate in the Black Sea, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East.

With the rift between the US and Turkey deepening, Europe should try to forestall a strategic rupture between Turkey and the West. Of course, Turkey is reliant on the EU, as the Union is Turkey’s largest export market, and its alignment with EU rules and its customs union with the EU has made foreign companies more willing to invest and contribute to the country’s rapid economic growth. But these links might not prevent relations from getting worse. Aside from tensions over Syria, EU-Turkey relations have nosedived as a result of Turkey’s oil and gas exploration efforts in waters the EU considers part of Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone. The EU is set to sanction Turkey for this, targeting individuals and entities involved. Even if Turkey halts its Syria operation it will be difficult for the EU and Turkey to avoid further tensions.

The EU should try to prevent a much broader rupture between Turkey and the West which would directly undermine Europe’s security.

EU member-states are frustrated and angered by Turkey’s behaviour, but they should be careful not to make decisions on the basis of irritation rather than calculation. A worsening of relations risks further undermining EU-Turkey co-operation on migration, at a time when the EU can ill-afford an increase in the number of migrants. The EU will continue to rely on Turkey’s co-operation: once Russia and Assad take over the last parts of Syria not under their control, as they eventually will, this is likely to create more refugees, many of whom will try to make their way to Europe. And, while ending Turkey’s bid for EU membership may seem like a tempting answer to Ankara’s operation against the YPG, formally terminating negotiations at a time of such discord, and without an alternative framework in place, would further sour relations, escalate tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean and weaken pro-European sentiment in Turkey. This could push the country further towards Russia and entrench authoritarianism at a time when opposition parties are gaining ground, winning elections in both Istanbul and Ankara.

The EU should reverse its July 2019 decision to halt high-level dialogue with Turkey – not talking only increases the chance of miscalculation. Brussels will not be able to exert any influence on Turkish policy towards Syria and the wider region unless the two sides resume talks and rebuild trust. The EU should also take steps to preserve its refugee co-operation deal with Turkey. Its funding to support Syrian refugees in Turkey is due to run out at the end of 2019. Of course, the EU should ensure none of its funds are used to resettle Syrian refugees in Ankara’s proposed ‘safe zone’ in northern Syria. But, by increasing its support for refugees in Turkey, the EU may also be able to steer Turkey away from the idea of resettling them in the zone.The EU cannot save the bilateral relationship on its own – this will also require Ankara to halt its offensive in Syria and take constructive steps to improve the rule of law. But it is in the EU’s interests to try to prevent a much broader rupture between Turkey and the West which would directly undermine Europe’s security.

Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment