EU border carbon adjustment: Proposed models and the state of play

The EU intends to introduce a border carbon adjustment (BCA) mechanism by the end of 2021. But questions remain as to whether a BCA is needed; whether it would be compliant with the EU’s World Trade Organisation commitments; whether it will be overly burdensome for business; and whether it will further destabilise the international trading system. However, without a BCA, the EU member states are unlikely to support ambitious action to reduce EU CO2 emissions.

The European Commission intends to introduce a border carbon adjustment mechanism (BCA) as part of its broader package of measures designed to help the EU become carbon neutral by 2050. A BCA would see a charge or levy proportionate to the carbon content of imported goods applied at the Union’s border, to guard against so-called carbon leakage.

However, introducing and implementing an EU-wide BCA will prove challenging. It will probably face legal challenge at the World Trade Organisation (WTO); create additional costs for businesses small and large; and risks further destabilising the international trading order. However, if carefully designed, a BCA could have a positive and complementary role to play vis-à-vis broader EU climate change policy, but the EU will need to tread carefully.

1. Rationale for a BCA

Carbon leakage – when companies transfer economic activity from countries and jurisdictions with strict emission regimes to those with weaker – has long been a concern of many EU member states, and has been used to justify opposition to new measures to combat climate change. However, there is little evidence to suggest that carbon leakage from the EU has been growing in recent years, and where industry has moved production abroad there are multiple other factors to consider, including, for example, labour being significantly cheaper in countries such as China.

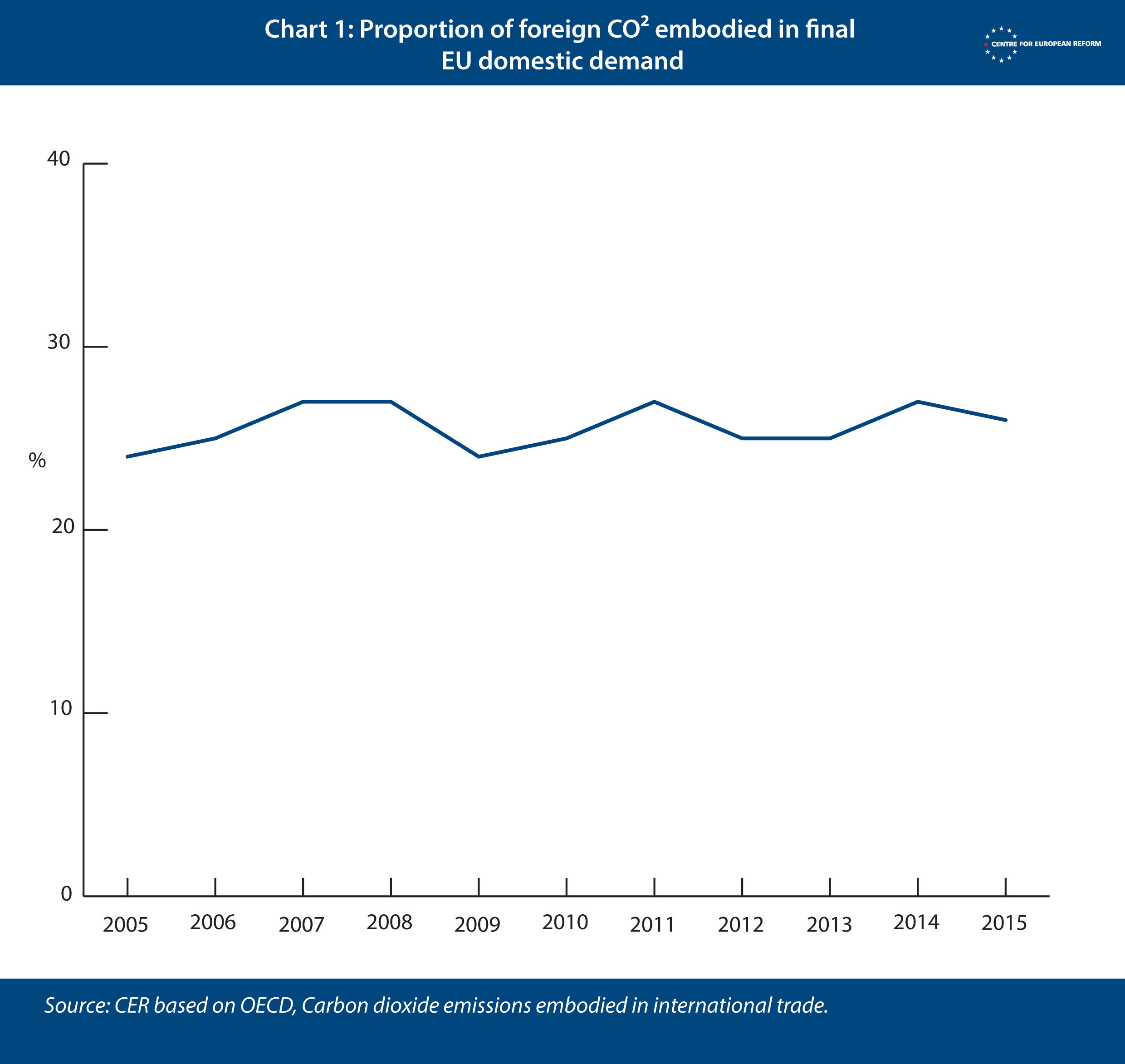

The OECD finds that the proportion of foreign CO2 embodied in final EU domestic demand has remained relatively constant, at around 25 per cent, in recent years (Chart 1) despite new EU measures such as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and Renewable Energy Directive coming into force during the observed period.

.

A Bank of Finland policy brief (Simola, 2020) finds that while (according to their calculations) the proportion of CO2 embodied in EU imports has increased between 2000 and 2014 there is little reason to think that this increase is primarily because of carbon leakage.2 They note that imports of final goods from China, for example, largely originate from sectors such as textiles, computers and electronics and electrical equipment that are not particularly carbon intensive.

However, imports of inputs destined for EU-based supply chains tend to originate from more carbon intensive sectors, which might point to some degree of carbon leakage.

The lack of evidence that carbon leakage has been growing leads some to argue that in the context of the EU’s Green New Deal, the BCA should be deprioritised because it offers “much pain, little gain”3. However, just because carbon leakage has not materialised yet, that is not to say that new, more ambitious, emission reduction measures could not create an issue in the future. Before prices collapsed during the COVID-19 economic lockdown, a tonne of carbon in the EU was priced at roughly 28 USD (the price of a carbon permit for one tonne of carbon under the EU ETS). But, according to the IMF, if global temperature rise is to remain below 2 degrees, a carbon tax of around 75 USD per tonne will need to be in place by 2030.4 Were the EU to unilaterally take measures to more than double its domestic price of carbon, the opportunities for arbitrage vis-à-vis jurisdictions with a lower carbon price will inevitably be larger than now.

Additionally, there are specific concerns – with politically sensitive European sectors such as the fossil-fuel industry, steel and other metals, and chemicals expected to perform worse in a world in which the EU acts unilaterally to reduce emissions than one in which action is taken globally.5 This means that for some member-states, which are more reliant on sensitive sectors, the fear of carbon leakage is felt more acutely. And in the context of a world in which the US (and to some degree, China) are failing to pull their weight on greenhouse gas reduction, if the EU is to unilaterally continue to raise its ambition, it needs to be able to assuage the fears of more vulnerable member states. It is noteworthy that Poland, one of the member states that has traditionally opposed ambitious EU-wide emissions reductions, is supportive of a BCA in principle; Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said “They help keep the industry in Europe. We don’t want the production of cement or fertilizers to move in a moment to Ukraine, Belarus, or India or China”6.

Ambitious multilateral action to address climate change is preferable, but it is unlikely without US leadership. In an imperfect world a BCA could serve two purposes for the EU: internally it provides political cover for ambitious measures to reduce CO2 emissions at both the EU and member-state level, and it provides a mechanism for the EU to leverage its market size to increase pressure on third countries to reduce emissions to ensure their exporters aren’t penalised when selling into the EU. Taking into account the current political climate, there is a risk that were the EU to backtrack on its plans for a BCA (or at least talk of a BCA), the internal political will to deliver the broader Green New Deal package will weaken.

2. Making an EU BCA work

The EU is exploring different approaches to creating a BCA. The European Commission intends to finalise its proposal by the second quarter of 2021. Options under consideration include a carbon tax on selected products, a new EU Border Carbon Adjustment: Proposed models and the state of play carbon import duty or an extension of the ETS to importers.7 However, no matter the policy instrument at the border, the Commission will want it to be compatible with the EU’s existing internal carbon pricing mechanisms, in particular the ETS.

Most probably, an EU BCA will see importers required to pay an import duty equivalent to the cost faced by the average EU-based producer when purchasing the necessary ETS carbon permits to produce a similar product domestically. (The price of imported carbon would need to take into account that a number of ETS permits are currently given to EU companies for free, although these ought to be phased out over time as the BCA renders them redundant.) The BCA would only apply to imports originating from countries not deemed to have an equivalent carbon price to the EU or products the importer is unable to certify were produced more carbon efficiently than the internal EU average.

On paper, there are simpler ways to design a BCA. For example, Guntram Wolff of Bruegel suggests a BCA mechanism that would operate in a similar manner to VAT: a carbon tax would be applied to all products consumed in the EU, no matter their place of origin. As such, as happens with VAT, the carbon tax would be payable by importers and refunded to exporters.8 While this would certainly be the optimal approach if starting from scratch, in the EU context it is probably not feasible. From a competence point of view, a direct tax would require unanimity in the Council, making the creation of a BCA more politically difficult. More pertinently, it would need to replace, and require the removal of, all existing carbon pricing mechanisms, including the ETS, which given the money and political energy spent on their creation is not an appealing prospect for many EU law makers. A complete overhaul of the EU’s approach to pricing carbon would also take time, and invariably delay the introduction of new measures and the European Green Deal.

3. Challenges facing an EU BCA

3.1 Legal difficulties

An EU-wide BCA will probably face legal challenge at the WTO from members that fear their exporters will become less competitive within the EU as a result of BCA-induced additional costs. Yet BCAs are an untested area of WTO law, and opinions differ as to the legality.

Jennifer Hillman, a former WTO appellate body judge, argues that to design a BCA that fully complies with the law, it should be non-discriminatory.9 This means that it should treat all products originating from its trading partners, as well as its own and like-foreign products, in the same way. Hillman says that “the key is to structure any accompanying border measures as a straightforward extension to the domestic climate policy to imports”. The EU will argue that while a BCA would not be a direct extension of its domestic ETS, GATT Article II.2 (a) allows for a WTO member to levy an additional tax on imports so long as it is equivalent to the cost imposed on domestic industry by an internal tax or similar.

To ensure it has the best chance of winning any dispute, the EU should ensure that the process for determining whether third country carbon pricing regimes are equivalent to the EU’s and exempt from the BCA is transparent and open, and allow countries to appeal its decisions. It should also put in place measures making it as easy as possible for imports of products produced carbon efficiently to be certified as exempt from any BCA charges.

The EU also might consider only applying the BCA narrowly in the first instance to a small number of emissions-heavy sectors, and make its coverage subject to regular review. To begin with, this could see the BCA applying to a relatively uncomplicated sector like cement, with short supply chains.

3.2 Complexity and costs

There is then the issue of complexity. Calculating the embedded carbon within a given product, with inputs potentially originating from many different countries and regulatory jurisdictions, is not easy and it would probably be expensive. Importers might find that the cost of demonstrating that their product has lower embedded carbon than the EU average, and therefore deserves a reduced rate, is higher than the default carbon levy.

The EU should take on board much of the financial and administrative burden, particularly for small and medium-sized companies. This could involve the Commission funding the creation and continued support of third-party certification bodies able to provide an objective assessment of a company’s CO2 emissions. Some of this money would be recouped from BCA tax revenues. But raising money should not be the objective: the aim is to allow Europe to become more ambitious on tackling climate change without risking economic damage – and to strengthen incentives for other countries to shift towards low carbon production instead of undercutting European environmental standards. There would also need to be origin-based criteria that determine exactly how much work needs to be carried out on a product in a given territory for it to qualify as originating from that jurisdiction. This could be determined using the pre-existing method for determining non-preferential rules of origin which all EU importers already have to follow.

3.3 Destabilisation and retaliation

Perhaps the most difficult question to answer is what impact an EU BCA would have on an already fractious multilateral trading regime and global business environment, which will also be suffering from the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. With tariffs already on the rise and the WTO appeals body no longer available a BCA that is seen as backdoor European protectionism would sour relations further. Rather than rely on the WTO dispute settlement process to iron out the legalities, a clumsily introduced BCA could see third countries retaliate unilaterally against EU exporters.

It could also provoke the US to retreat further from trade multilateralism andmake it harder for the EU to secure free trade agreements with some partners.For example, if eventually extended to cover agriculture, ratification of the EU’sagreement with the Mercosur trade bloc, in particular by Brazil, could becomeimpossible. As well as the US, a BCA might provoke China if it is deemed tounfairly single out Chinese products – and the process of determining whetherChinese domestic measures on climate are equivalent to the EU’s could create diplomatic tensions.

There is also the issue of fairness. While all signatories to the Paris Agreement on climate change have agreed to take action to reduce emissions, developing countries have been given extra leeway because they have historically contributed far less to global emissions than industrialised countries. Any border adjustable carbon tax should take this into account. Countries currently covered by the EU’s ‘everything but arms’ scheme, which gives tariff and quota-free access to the EU market to least developed countries, could be exempted, for example.

4. Conclusion

Designing an effective EU BCA mechanism is not without its challenges. Whether it is compliant with the EU’s international obligations, and not unduly burdensome for businesses will be dependent on its design. Yet, if multilateral action on climate change fails to progress because of US inaction or otherwise, a BCA can play a vital role in both cajoling third countries into continued action, and providing political cover for ambitious unilateral emissions reduction measures within the EU.

3 Zachmann, G., McWilliams, B., (2020), A European carbon border tax: much pain, little gain. Policy Contribution 05/2020, Bruegel https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PC-05-2020-050320v2.pdf).

4 IMF, (2019), Fiscal Monitor: How to Mitigate Climate Change. Washington, October. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2019/10/16/Fiscal-Monitor-...

2019-How-to-Mitigate-Climate-Change-47027.

5 Lowe, S., (2019), Should the EU tax imported CO2?. Centre for European Reform. https://www.cer.eu/insights/should-eu-tax-imported-co2.

6 Larger, T., Tamma, P., Leali, G., (2020), POLITICO Pro Fair Play: Carbon border tax –Don’t call them champions – Wind. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/politicopro-fair-play-carbon-border-tax-....

8 Wolff, G., (2019), Why border carbon adjustment is important for Europe’s green deal. Bruegel.

https://www.bruegel.org/2019/11/a-value-added-tax-could-reducecarbon-lea....

9 Hillman, J., (2013), Changing Climate for Carbon Taxes: Who’s Afraid of the WTO?.

Climate Advisors. https://www.climateadvisers.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2013-07-Chang....

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

This is a chapter from 'Schwerpunkt Außenwirtschaft 2019/2020 Internationaler Handel und nachhaltige Entwicklung', ONB, you can read the full publication here.