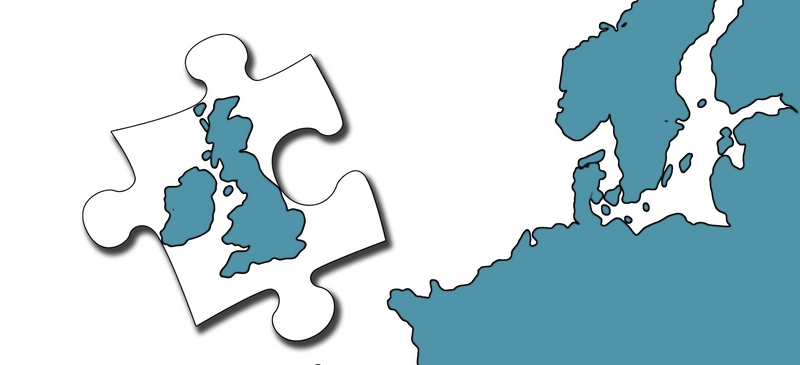

Is Britain on the way out of Europe?

Ever since they joined the EU in 1973, the British have been sceptical about political integration in Europe. They have valued the economic benefits of membership, notably the single market, but opposed the concept of ‘political union’. The eurozone crisis is now increasing the gap between Britain and much of the rest of the EU. The countries in the eurozone are going to have to co-ordinate economic policy much more closely and give more authority to supranational institutions. In Germany, many politicians are talking about a ‘political union’.

A politically-integrating core will make the EU less congenial to the British, and increase pressure for a referendum on withdrawal. Many members of the governing Conservative Party want such a referendum. Its leaders are opposed, since a referendum would split the party and be a distraction from sorting out the economy. But future leaders may well choose to give party members what they want.

The growing euroscepticism of the Conservative Party reflects the evolution of British public opinion. Only in 2011 did opinion polls start to show a clear majority for leaving the EU. The euro crisis has made a big difference. Eurosceptics always said that the euro would lead to disaster and they can now claim they were right. Furthermore, Europe’s leaders have shown themselves to be incompetent: countless emergency summits and rescue packages have failed to solve the eurozone’s problems.

Many Conservatives – and the small businesses that are close to the party – have come to view the EU as a source of red tape, a hyper-bureaucratic organisation that stifles free enterprise and a slow-growing economic bloc that drags down the performance of an inherently dynamic British economy. Some of them see the future in stronger bilateral ties with the BRICS and North America – ignoring the fact that Britain exports more to Ireland than to all the BRICS together.

The City of London, in particular, worries that Paris and Berlin are trying to use new EU financial regulations to steal or shackle its activities. Many British people have no great love for bankers, holding them responsible for their economic woes. But a lot of financiers – who are often close to senior Conservatives and editors – have become eurosceptic. They fear, in particular, that the Commission proposal for a financial transactions tax – an idea strongly backed by France – could push a big chunk of their business outside the EU.

Migration, a toxic political subject, has also fuelled euroscepticism. Britain was the only member-state (apart from Ireland and Sweden) to let in people from the Central European states as soon as they joined the EU in 2004. More than a million arrived, causing much resentment in some communities, and the EU was blamed.

Well-funded and effective lobbying groups, such as Open Europe, bolster the eurosceptic cause, while their pro-EU equivalents lack muscle. Many large companies remain pro-EU but are reluctant to speak out, lest they annoy the government. For example, after the December EU summit left Britain excluded from the new ‘fiscal compact’, senior foreign bankers in London said in private that the British government would have less influence on future EU financial legislation. But none of them would say so on television.

What can be done to arrest Britain’s slide towards the exit? Business leaders should highlight the benefits of membership – such as increased foreign direct investment, and the ability to shape the rules of the world’s largest single market – and put money into pro-EU lobbies. Trade unionists also have a role to play. Many of them welcome rules from Brussels on working hours and maternity rights but seldom champion the EU.

Politicians of left and right are fearful of defending the Union lest it cost them votes. They need to find the courage to spell out how the economy gains from membership. And when the Union achieves something in the wider world – such as negotiating a trade deal with South Korea, brokering a global climate agreement in Durban or forging an oil embargo against Iran – politicians should explain how it amplifies Britain’s voice.

The British government should come up with positive ideas for the EU – and not only further enlargement (on which it has little support) or the deregulation of services and the digital economy (on which it has allies). Constructive ideas on climate, energy, the neighbourhood, foreign policy or defence would make it easier for Britain to forge alliances with like-minded countries, such as the Nordics, Poland, Italy, and – on some issues – France and Germany. Such alliances would enhance Britain’s ability to set the Union’s agenda and thus win the arguments in Brussels. This would help to refute the eurosceptic assertion that the EU works against British interests.