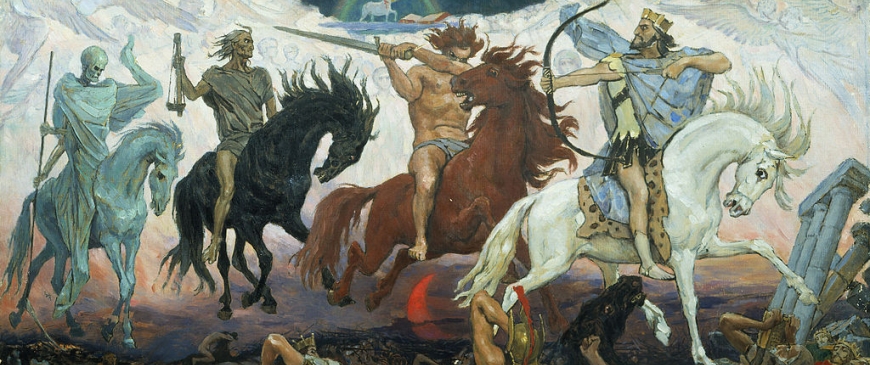

The four horsemen circling the European Council summit

Simultaneous crises are the new normal. Europe’s leaders must confront a quartet of challenges if they want to prevent the European Union falling apart.

Four horsemen will be circling around this week’s European Council. They represent four crises that threaten the EU: ‘Grexit’; the Mediterranean migration crisis; Russian aggression; and Britain’s threat to leave if the club is not reformed. Any of these issues could dominate the European Council’s agenda: each could alter the fundamental character of the Union. While none of them is particularly new – Greece's economic and financial woes have troubled the EU for six years – they are circling together and affecting each other.

‘Grexit’ looms first. The risk of a Greek default and possible exit from the eurozone is the most acute of the four crises. Over the past several months, Greece’s creditors and the government of Alexis Tsipras have played a dangerous game of chicken. As a deadline approaches for Greece to repay the IMF €1.6 billion, it seems Greece may give in. An emergency summit on Monday brought renewed hope for a deal, as Greece offered more cuts to pensions and higher taxes. Tsipras now faces an uphill battle in the European Council to convince sceptical creditors like Germany and Finland, or fellow debtors like Spain and Portugal. For a deal to stick, the Greek leader must persuade sceptical members of his own party that he is not caving in to demands from Brussels. But even if a deal is clinched, as CER’s Christian Odendahl recently pointed out, a lasting solution to Greece’s economic problems will remain elusive. And so, despite the brinkmanship of the past weeks, even if Europe’s leaders hammer out an accord with Greece they may simply buy more time rather than remove the risk of Grexit.

Russia hovers over the ‘Grexit’ talks too. Should Greece leave the eurozone, it will need to attract credit, loans and investment from elsewhere, and Russia has shown an interest. This has strengthened Tsipras’ hand in the negotiations with Brussels. On Friday June 19th, the day after the Eurogroup failed to reach a Greek bailout agreement, Tsipras flew to Saint Petersburg for a meeting with Russia’s president Vladimir Putin and Alexei Miller, the head of Gazprom. The Greek leader signed a preliminary agreement to build a $2 billion pipeline across Greece, as part of Gazprom’s ‘Turkish stream’ project. The agreement is non-binding, but pokes a finger at the Commission’s plans to reduce the EU’s dependence on Russian gas imports. Tsipras’ flirtation with Moscow, at a time of high stakes negotiations with Brussels, has raised eyebrows. An increasingly Russia-friendly Greece would make it more difficult for the EU to maintain a unified position against Russian assertive behaviour in Ukraine and Eastern Europe.

Meanwhile, people continue to die on a daily basis in Ukraine’s ongoing conflict, though at less alarming rates than before. The ‘Minsk-II’ ceasefire is flawed, but most European governments are unwilling to give up on it. They think Russian help is needed elsewhere, such as the Iran nuclear talks and the Syrian civil war. As long as the fighting does not escalate dramatically, European leaders will not step up pressure on Russia to change its behaviour. Some leaders worry about the impact of sanctions on business (though statistics show the effect is limited), and argue that the current lull warrants a thaw in relations with Moscow. While France has cancelled the controversial sale of the Mistral amphibious ships, three European oil and gas companies have recently struck new commercial deals in Russia.

For now, however, the EU remains politically unified: most of the sanctions have been extended until January 2016, while those specific sanctions linked to the annexation of Crimea have been rolled over for a year. That unity may not endure, however. Regardless of what happens in the Donbass, by the end of the year, investigators will have published their official findings into the shooting down of flight MH17, which killed 298 people. One potential finding of the report could point to Russian complicity, either in delivering the missile system, or in the chain of command that led to the missile’s firing. European leaders will then need to decide whether to punish this crime or do nothing. A push for new sanctions could strain today’s delicate unity on Russia, while inaction would be a sign of weakness and an insult to the victims. The creation of an international tribunal to persecute the culprits may offer a sensible, but unsatisfying, middle road.

The desire to avoid ruffling Russian feathers means that Ukraine will not figure prominently at the European Council meeting either. But that is a mistake. Ukraine needs money: earlier this year Kyiv said that it required some $40 billion over the next five years, to avoid economic collapse, but with the economy continuing to deteriorate that sum now looks inadequate. As Charles Grant and Ian Bond have highlighted, some of that money is coming from the IMF, and some may eventually come via debt restructuring, but most of the money will need to come from the EU and the US. If Ukraine’s economy collapses, the ensuing political chaos would threaten the pro-Western leadership in Kyiv, handing Vladimir Putin the victory he has not been able to achieve through military force.

4 horsemen will be circling this week’s EU summit: Grexit, migration, Russia and Brexit

The third horseman circling is the migration crisis in the Mediterranean. In the first six months of 2015, 1,868 migrants have died trying to cross from North Africa. According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), some 114,000 migrants have reached Europe, mostly landing in Greece and Italy. In summer the weather is calmest and crossings increase, so both numbers are likely to rise. In response, the EU is trying to look tough. On June 22nd, it launched an Italian-led mission to monitor the maritime movements of smugglers. A subsequent stage of the operation would see European navies board and seize migrant ships, including in Libyan waters. Diplomats in New York are currently drafting the necessary United Nations mandate. The EU also wants the permission to destroy ships used by traffickers, although this is not likely to get international or Libyan support.

None of these measures will solve the migration crisis. The EU should take a broad approach, in terms of geography and reach. It will not be enough to track smugglers’ movements at sea, although it is a start. Gathering accurate intelligence on smuggling networks requires a presence on land or a credible Libyan counterpart with which to co-operate. And a focus on Libya makes sense at first, but smugglers could soon exploit the route of least resistance by shifting their activities to other parts of the North African coast. Many migrants are Syrian refugees, but a solution to Syria’s civil war remains out of reach. The EU must also review its development and humanitarian policies in transit countries like Libya, and in source countries across the African continent. A humanitarian tragedy cannot be reduced to a mere security challenge.

The tough debate in the European Council will, however, be less about the military mission or the EU’s foreign policy response, and more about migration’s ramifications within the EU. In May, the European Commission proposed a quota system, which would alleviate the burden on countries such as Italy and Greece, and redistribute 40,000 asylum seekers across the EU. Many, including the Central and Eastern European countries, object to this mandatory system. Under quotas, they would receive many more migrants than would otherwise be expected to make their way to them. Northern member-states also object because they ultimately feel these asylum seekers should be processed in southern Europe. Italy feels abandoned by the rest of the EU and has threatened to give migrants temporary visas so they can travel to other member-states. France has retorted that this might trigger the re-imposition of French border controls. The Schengen border code allows temporary border controls in exceptional circumstances, such as in the event of a serious threat to the internal security of a member-state. But in this case its invocation would not be the result of an acute threat to internal security, but of the breakdown of European solidarity. All this could cause a serious Schengen crisis, and draw into question one of the foundations of the EU – the free movement of people.

That leads to the fourth issue, which although not a crisis (yet) will preoccupy European leaders for the coming year. Britain’s prime minister, David Cameron, will outline his EU reform agenda at the summit meeting. He hopes to get results before an in-out referendum on EU membership, which may well take place in autumn 2016.

Among other things, Cameron wants to cut EU migrants’ access to benefits (particularly those going to people in work), in the hope that this would deter people from coming to the UK. This puts him on a collision course with several member-states, including Germany and Poland, which point out that this would violate EU treaty articles banning discrimination on grounds of nationality. The other member-states are very reluctant to open up the treaties to accommodate British reforms. They fear that one or other member-state would grab the opportunity to make special demands themselves. In some countries, like France, Ireland and the Netherlands, treaty change would trigger risky referendums. Cameron’s dilemma, however, is that a lot of Conservative backbenchers will not support his effort to keep Britain in the EU unless he achieves radical change.

Other British ideas may go down better in Europe, such as strengthening the EU’s ‘competitiveness’ by trimming cumbersome regulation, negotiating free-trade agreements and deepening the single market. The forthcoming European Council gives Cameron a platform to launch his renegotiation campaign, though for now he will avoid going into the details of what he wants. The secretariat of the Council of Ministers will be tasked with taking forward the detailed work, together with British officials. Cameron will find it hard to convince his European colleagues that they need to change EU policies and institutions in order to help him. As Charles Grant wrote recently, member-states fear that Eurosceptic backbenchers will push Cameron into demanding reforms that are unobtainable. The fewer allies Cameron has in the Europe, the tougher the negotiations will be, and the more the ‘British question’ will become an irritant in European politics.

The EU’s leaders will find it hard to tame these four horsemen. No country can afford to pick and choose which of these issues to take seriously and which not. All four are dangerous, and they all require a coherent European response. The four horsemen threaten the EU precisely because they raise issues that can only be solved if governments prioritise a European solution over narrow national agendas. If a European answer cannot be found, the horsemen will continue to promote chaos, instability and mutual recrimination within the EU.

Rem Korteweg is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.