Ten reflections on a sovereignty-first Brexit

The UK-EU trade deal prioritises sovereignty over economics. Politicians will soon be talking about how to improve the deal. Very little about the UK’s long-term relationship with the EU has been settled.

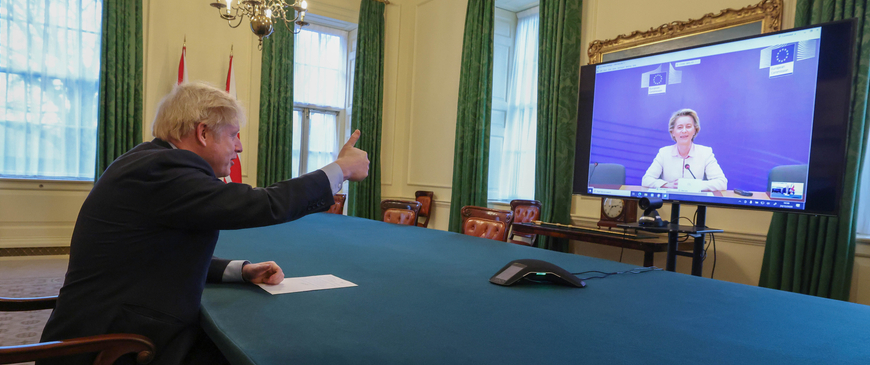

One particular comment that I heard during the Brexit negotiations has lodged in my memory. In September 2020, a senior EU official working on Brexit said to me, with exasperation: “What is so weird about the British approach to Brexit is that when you talk to the guys in Number 10, they just don’t care about the economy; freedom from EU rules and courts is all that matters to them.” That denigration of economics helps to explain why the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA), finalised by Boris Johnson and Ursula von der Leyen on Christmas Eve, promises to deliver such a hard – or sovereignty-first – Brexit. The good news about the TCA is that the alternative of no deal would have been much worse for both the EU and the UK. The bad news is that the deal will diminish not just Britain’s economic ties to the continent, but also security, educational and human connections. Here are ten reflections on the Brexit process.

1. Achieving a free trade agreement (FTA) in ten months is unusually quick.

Normally it takes the EU around five to seven years to negotiate an FTA. David Frost, Michel Barnier and their respective teams deserve congratulations for their perseverance and hard work. In one respect, the UK’s refusal to extend the transitional period beyond the end of 2020 may have helped, by concentrating minds. But in another respect that decision was questionable, since businesses have faced massive uncertainty and now have just a few days to adjust to new arrangements. It is inconceivable that everyone will be following the new rules on January 1st 2021.

One reason why the deal was done quite speedily is that political leaders were more engaged than is common in FTA talks. But the negotiators could probably have moved even faster, had their political masters allowed them: much of the past three months has involved posturing for the benefit of domestic audiences. It probably suited both camps to leave the final compromises until the last moment, to show those audiences that they were fighting tenaciously, and to minimise the time for potentially awkward scrutiny in the UK and European Parliaments.

2. Most British people have no idea how hard Brexit will be.

Over the four-and-a-half years since the referendum, the British people have – understandably – become increasingly bored with the tedia of the Brexit negotiations. Many of them switched off long ago and assume that a deal means that things will be alright. They are right that no deal would have led to much more disruption. But a lot will change – and much more than most leading Leavers promised during the referendum campaign.

Most British people have no idea how hard Brexit will be. When they realise, politicians will start talking about how the deal can be improved.

Manufacturers and farmers will face irksome checks at borders for things like customs, VAT, safety and security, plant and animal health, and much else. Services companies will lose access to the single market unless they set up subsidiaries within it. British airlines and freight firms will no longer be able to operate freely within the EU. Citizens will lose the right to travel for as long as they wish, work, study or reside in the EU. Industries and institutions that have become accustomed to employing EU citizens – including farming, food processing, hospitality, care homes, construction and universities – will face difficulties. Britain is leaving a plethora of EU agencies, such as those that deal with medicines, chemicals, air safety and food safety. The British police will lose direct access to many EU criminal databases.

3. It turns out that leaving the EU is rather like accession in reverse.

When seeking to join the EU, a prospective member has to take the EU’s terms or it doesn’t get in. Similarly, once the UK had worked out what its red lines were, the EU decided on the shape of the deal it would offer: in essence a Canada-style FTA, but with a broader scope, covering areas like energy, and justice and home affairs; with stricter rules on subsidies, the environment, climate and labour standards, tied to enforceable conditionality, so that trade preferences can be withdrawn if either side breaches commitments; and rather less generous provisions in certain areas (such as the minimal coverage of financial services, the absence of mutual recognition of certification bodies and stricter checks on food imports). The UK signed up to all this, because it held fewer cards than the EU: no deal would have hurt it more than the EU.

The analogy is not exact, because the UK had more leverage than say Montenegro has in seeking to join the EU. That is why the EU softened some of its initial demands, for example that the UK should follow its state aid rules, or that the European Court of Justice should play a role in policing the deal. But in the final phase of the talks the UK ceded on some important issues like fish – during a transition period the EU will ‘hand back’ only a quarter of the fish it currently takes from British waters; and rules of origin – the EU will not allow ‘extended cumulation’, meaning that components from countries with which the UK and the EU have FTAs (like Japan) will not count as local content, making it harder for UK-made products to qualify for zero tariffs.

4. For the past four-and-a-half years, British governments have seldom been honest about the trade-offs that Brexit involves.

Any country leaving the EU has to choose a place on a spectrum between, at one end, maximum regulatory autonomy and minimal economic ties, and at the other, minimal regulatory autonomy and maximum economies ties. The trade-off is between sovereignty and prosperity. Being honest would have required an admission that Brexit carries real economic costs. In private, some Brexiteers, including those in the government, admit as much – though most of them would add that in the long run the economy will thrive when freed of Brussels rules. But they could not be so honest during the referendum campaign or they might have lost.

To be fair to Boris Johnson’s government, it has in some ways been clearer about the trade-offs than that of Theresa May: for some time it has admitted that leaving the customs union means frictions at the UK-EU border, with implicit economic costs. But Boris Johnson’s post-deal victory speech, in which he falsely declared the deal would mean "no non-tariff barriers", suggests a government still struggling to fully understand the consequences of its decisions.

5. Future historians will ask why the British government paid so little attention to economics during the negotiation.

The short answer, evidently, is that Johnson’s government of hard-Brexiteers prioritised sovereignty and chose to sit at one end of the spectrum referred to above (May’s government had wanted to sit further along the spectrum, seeking to preserve some benefits of the customs union and single market).

Future historians will ask why the British government paid so little attention to economics during the negotiation. The short answer that Johnson’s government prioritised sovereignty.

It is nevertheless strange that a country which helped to invent economics and has free trade in its DNA paid little heed to the needs of key pillars of the economy such as the City of London and the car industry. To many Brexiteers, the fishing industry, which contributes just 0.04 percent to UK GDP, mattered more, and indeed the talks came close to collapse over fish quotas.

The cause of business suffered from the fact that most of its leaders had been Remainers – which made them persona non grata in the higher reaches of government. I was present when Foreign Secretary Johnson – at a diplomatic reception – said “F*** business.” And David Davis, May’s first Brexit secretary, was no politer when he spoke about the City of London. One must acknowledge, however, than many civil servants dealing with Brexit worked hard for the interests of the British economy.

6. The EU has been unduly paranoid over the ‘level playing field’, which proved one of the most contentious issues in the talks.

Britain has an £80 billion a year trade deficit with the EU, which suggests that European fears of a hyper-competitive Britain distorting the single market are exaggerated; if anything, it is the UK that suffers from a playing field tilted against it (many services, where the UK excels, were never properly liberalised by the EU). Furthermore, as already explained, Brexit is bound to make the UK less competitive and therefore less attractive to foreign investors.

Faisal Islam, the BBC’s economics editor, summed up the EU’s point of view in a tweet: “The UK is declaring regulatory independence while trying to maintain zero tariffs; the EU is trying to manage that divergence and prevent for example the UK becoming an offshore assembly hub for American and Chinese firms with free single market access.” The EU’s worries over the level playing field are genuine. For several decades an item of faith among French policy-makers has been that the UK would steal investment from the continent through ‘social dumping’, that is to say cutting labour market standards, but there is scant evidence to back up that thesis.

British politicians have done their best to provoke European fears. May’s chancellor, Philip Hammond, a moderate Remainer, talked of creating ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ post-Brexit. More recently a group of advisers in Number 10, associated with Dominic Cummings – who was until November Johnson’s chief aide – have had a vision of a deregulated Britain that thrives through being not-the-EU (Cummings also talked of using large amounts of state-aid to nurture high-tech industries).

However, the political reality is that no British government, even a right-wing Tory one, is going to slash social and environmental protections (or overturn the longstanding British aversion to industrial subsidies). Such protections are too popular with Conservative voters and indeed a majority of the party’s MPs. For those of us who wish the EU well, its lack of confidence in the viability of its own economic model against stern competition is a little worrying.

7. When the British people realise what a thin deal they have got, their politicians will debate whether and how to improve it.

If, as I expect, the TCA proves a major inconvenience for significant groups of people, businesses and institutions, a debate will start on how to improve it. The TCA includes a clause allowing either party to request a review of the provisions on trade, four years after it enters into force – which will make the EU-UK relationship a theme of the general election that is likely in three or four years.

It is possible that the Conservative Party will rediscover its liking for big business, in which case moderate MPs will argue for a more business-friendly agreement. But if the Tories remain imbued with nativist-nationalist attitudes, they will be relatively indifferent to the views of industrial lobbies. It would then be left to the Labour Party to argue the case for closer ties. On the one hand, Keir Starmer may be reluctant to do so, given that he is trying to enhance support for his party in northern, Brexity parts of the country. On the other hand, Labour members are mostly pro-EU and the party has longstanding ties to manufacturing – which will be making a strong case for rejoining some sort of customs union with the EU.

Meanwhile the police and the intelligence services will be arguing for closer co-operation on justice and home affairs. The possibility of forging structural links to the EU on foreign and defence policy – which the TCA ignores – will also be a matter for debate.

For one reason or another, the UK is likely to be in non-stop negotiations with the EU for decade after decade – as the Swiss have been since the 1970s. But one senior Swiss diplomat has a warning for British Remainers: since 1992, when Switzerland narrowly voted not to join the European Economic Area, support for EU membership has slumped from around half to not much more than 10 per cent. He points out that never-ending talks with a much stronger neighbour who sometimes behaves arrogantly have not made the Swiss Europhile.

8. In these semi-permanent negotiations, the UK will be hampered by a lack of trust on the EU side.

The behaviour of the past three Conservative prime ministers has weakened Britain’s standing vis-à-vis EU leaders. There was some decline when David Cameron was prime minister, with episodes such as leaving the European Peoples Party, refusing to sign the Fiscal Compact treaty and botching the referendum campaign. Respect for Britain fell further with May, because her divided government took two years to come up with a plan for Brexit and then failed to get her Withdrawal Agreement through Parliament. Britain’s soft power then diminished sharply with Johnson, whose words and actions have often dismayed Britain’s friends in the EU. To mention just two episodes that resonated outside the UK: his suspension of Parliament in the autumn of 2019 – subsequently ruled illegal by the UK Supreme Court; and his Single Market Bill in the autumn of 2020, including clauses that allowed the government to over-rule parts of the Withdrawal Agreement (concerning the Irish border) that it had recently negotiated with the EU. Johnson has now withdrawn the contentious clauses but much damage has been done. EU leaders do not trust his government to keep its word or respect international law.

In the UK’s future, semi-permanent negotiations with the EU, it will be hampered by the fact that EU leaders do not trust Johnson’s government to keep its word or respect international law.

Of course, EU leaders are pragmatic and will deal respectfully with any government that the British people choose to elect. But much of the goodwill that many of them felt for the UK has evaporated. It may return, if Britain’s leaders make a habit of being constructive in their dealings with the EU. But if Conservative governments seek to boost their popularity by bashing Brussels, the UK will find the EU a harder and more legalistic negotiating partner.

9. The question of the UK rejoining the EU is unlikely to be on the agenda for a generation.

Public opinion polls suggest that a clear majority of the British view EU membership positively. If and when people perceive the TCA to be a sub-optimal framework for UK-EU relations, even greater numbers may regret Brexit. But that does not mean there will be a strong desire for another referendum to reverse that of 2016. Many Remainers think that the country needs to make the best of a bad job and move on. Keir Starmer opposed Brexit and for a while supported a second referendum – but that was before Britain had left the EU. Now that he is trying to restore Labour’s credentials with Leave voters, Starmer is unlikely to want to campaign to rejoin.

Of course that could change if public opinion shifts dramatically. But then British rejoiners would face a problem with the EU. Most politicians in EU countries regret Brexit enormously. But they would not welcome a membership application from a Starmer government, if the Conservative opposition remained opposed to the EU. That is because there would then be a danger of Britain joining and leaving every few years. If there was a national consensus in favour of EU membership, European leaders would be interested. But there seems very little prospect of the Tory Party becoming pro-EU in the foreseeable future.

That condition for membership – a broad national consensus in favour – is more-or-less met in the case of Scotland. If Scotland were to gain independence through legal means, and then seek membership, most EU leaders would be delighted.

10. Brexit has made the future of the United Kingdom more uncertain.

During 2020, the year of COVID-19 and the Brexit trade talks, support for independence among Scottish voters rose substantially, to about 60 per cent. The pandemic and the trade talks allowed the Scottish National Party (SNP) to portray the Conservative government as incompetent and acting against Scotland’s interests. The more that Brexit appears to hurt Scotland, the better for the SNP and its policy of ‘leave the UK to rejoin the EU’.

The Scots noticed that during the referendum campaign and subsequently, few Leavers – with some exceptions like Cabinet Office Minister Michael Gove – cared much about the unity of the UK. Many Scots do not warm to the English nationalists who are so influential in today’s Tory Party. The SNP is on course for a big victory in May’s Scottish elections. Evidently, if prime ministers in London continue to say no to another Scottish referendum (as Johnson does), Scotland cannot become independent. But with every successive SNP victory, it will be harder for London to keep saying no. Brexit has made independence more likely.

The situation in Northern Ireland is more complicated. The Northern Ireland protocol of the Withdrawal Agreement puts the territory de facto in the EU’s customs union and parts of its single market, and also creates elements of a border in the Irish Sea, for goods travelling from Great Britain to Northern Ireland. These provisions preclude the need for controls on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic – but have annoyed the Unionist community.

There is much uncertainty about how these new arrangements will work in practice and whether they will prove stable. If Unionists find the new border controls an awful encumbrance, could a future Tory government tear up the protocol, as Johnson nearly did a few months ago? And with supermarkets in the north already shifting their supply chains from English wholesalers to those in Ireland, and economic links between north and south likely to multiply, will more of the Northern Irish start to favour a united Ireland? At the very least, the new arrangements create much uncertainty about Northern Ireland’s future.

Conclusion

The Christmas Eve agreement has settled very little about the UK’s future and its place in Europe, other than that it will be out of the EU for the foreseeable future. Many questions remain open. How much will British rules diverge from those of the EU? Will relations with the EU be friendly or acrimonious? Will they revolve around informal get-togethers of leaders, or non-stop arbitration? Will the UK seek closer ties to the EU on security, foreign policy and defence, or prefer links to the ‘Anglosphere’ countries? Will President Emmanuel Macron’s concept of a ‘Europe of concentric circles’, in which the UK could perch on an outer rim, take shape? And will the sovereignty-first school of Tory continue to steer the UK’s course, or will the ghosts of Smith, Ricardo and Keynes fight back, pushing the UK closer to its largest market?

Charles Grant is director of the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Again, thank you for this very illuminating analysis.

Thank you very much for your reflections.

I was wondering If one more aspect should be added to point number 9. In my view, there will be no more opt-outs in case UK will rejoin EU and this is something that remainers should take into account sooner or later in a possible future campaign.

Leaving the single market creates friction at the EU-UK border, even if the UK were to remain in the customs union. Just look at the Turkey-EU border, Switzerland-EU border, Norway-Sweden border or any border in the EEC before the single market was created in 1993.

Add new comment