Where is Britain's growth plan?

The government will have to confront vested interests and raise investment to boost growth. A strategy founded on trade deals with far-off countries and deregulation won’t work.

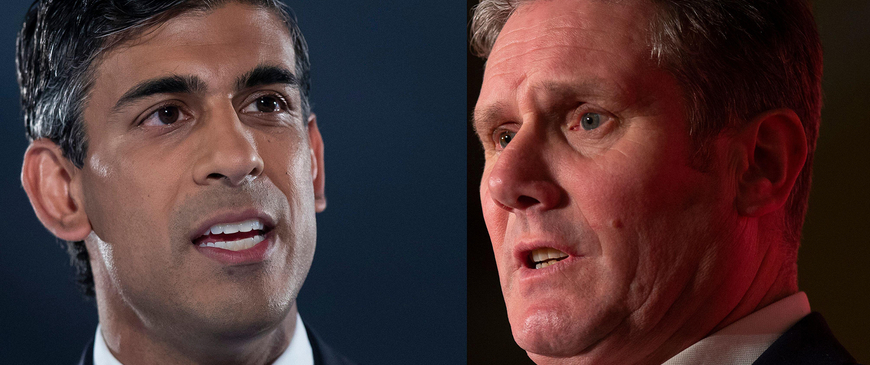

Britain’s economy is weak, but there is a strange lack of urgency in Westminster about the problem. Unlike most other advanced economies, economic output has still not returned to its pre-pandemic level. The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government’s independent fiscal watchdog, forecasts that living standards will not reach their 2019 level till 2027-28. But, in the run-up to an election that is likely to take place next year, neither the government nor the opposition Labour Party are setting out bold strategies to fix the UK’s economic problems.

Britain’s economy is weak. Unlike most other advanced economies, economic output has still not returned to its pre-pandemic level.

Finance minister Jeremy Hunt announced his budget on March 16th. His goal was to raise labour supply through more hours of free childcare, back-to-work policies, and pension changes to give older professionals more incentives to remain in work. However, this would only increase potential output by 0.2 per cent, according to the OBR. Meanwhile, Hunt plans to cut public investment by £15 billion relative to spending plans set out two years ago. Labour’s own economic plan is vague, promising to “secure the highest sustained growth in the G7”, but without much detail on how to achieve that goal.

What explains the lack of urgency? One obvious reason is that former prime minister Liz Truss pursued growth at all costs, and the markets reacted badly. Neither party wants to appear reckless during a period of high inflation and tightening borrowing conditions. Another reason is that Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system means a small number of floating voters in marginal constituencies determines the outcome. On average, those voters are older and more likely to own a house so they are less affected by weak growth than younger people. They are also more socially conservative, and more likely to support Brexit, so both parties are downplaying the economic consequences of leaving the EU.

There are many reasons for the UK’s economic doldrums. The country has been hit by a succession of crises since 2008. The financial crisis exposed an indebted economy with a large and globalised banking sector. Successive Conservative-led governments then failed to take advantage of low interest rates to invest in infrastructure and skills. Brexit has reduced the supply capacity of the economy by introducing barriers to trade and depressing investment, which had been recovering before 2016. The pandemic exposed the risks of an underfunded healthcare system. Britain consumes more gas per capita than most European countries, after years of underinvestment in alternatives and in energy efficiency, so it was in a weaker position when Putin invaded Ukraine.

This series of shocks laid bare the weaknesses of Britain’s economic model, and demands a comprehensive response. But a Trussite strategy – deregulation and tax cuts – cannot be the answer. The UK is one of the most lightly regulated advanced economies and voters do not want to cut public services. That pushed both Jeremy Hunt and his predecessor but one, Rishi Sunak, to raise taxes. Any growth strategy will have to focus on the economy’s real problems, and avoid the student union policies of Johnson and Truss. And it will require a lot of state investment: turning Britain around cannot be done on the cheap.

Any growth strategy will have to focus on the economy’s real problems, it will require a lot of state investment: turning Britain around cannot be done on the cheap.

The first problem is the use of land. The UK’s cities are less dense than their European peers, and its transport systems are more congested. Only 40 per cent of the residents of the UK’s biggest eight cities can get to the city centre by public transport in half an hour, while 67 per cent of the residents of comparable European cities can. Weak transport limits the labour pool for employers, because there are fewer potential workers who are willing or able to travel to each job. Employers’ needs and workers’ skills are therefore poorly matched, curbing productivity.

The government will have to face down opposition from NIMBYs (opponents of new buildings, who cry ‘not in my back yard’) and invest more in commuter transport, while encouraging denser housing, to make local labour markets bigger and more efficient. In his budget, Hunt announced an increase in local transport funding for the biggest city regions from £6 to £9 billion, which is good, but is unlikely to be enough to rapidly reduce journey times. And height restrictions for buildings across UK cities continue to limit density, but reform has been slow.

The second problem is highly unequal education and skills. As a share of GDP, the UK spends more than the OECD average on education at all levels. But that spending is not distributed progressively enough: pupils from poorer backgrounds need more resources to make up for the gaps in attainment that open up at an early age. In 2010, spending on the most deprived fifth of state primary schools was 35 per cent higher than the most affluent fifth, but by 2020, that premium had fallen to 20 per cent.

Meanwhile, spending on state school pupils stagnated between 2010 and 2020, at around £8,000 per pupil, while private school spending rose from £11,000 to £14,000. State primary school class sizes, at 27 pupils, are much larger than the OECD average of 20. All this may explain why, while British pupils’ numeracy and literacy scores are above the OECD average, the gap between low and high achievers is at the OECD average (in reading and maths) or worse (in science).

Third, the energy crisis has hit the UK particularly hard, because it uses more gas for heating and electricity generation than many of its European peers. The government has only mildly relaxed planning restrictions on onshore wind. Successive governments have not done enough to install insulation and heat pumps, which would reduce gas imports and create savings that households could spend on other goods and services. Only 60,000 heat pumps were sold in the UK in 2022, compared to 500,000 in Italy, 350,000 in France and 280,000 in Germany. Britain’s homes are among the least energy efficient in Europe, but only 300,000 out of more than 20 million houses will be eligible for new government grants for insulation.

To its credit, Labour is promising a rise in climate investment of £28 billion a year if it wins the next election. That is around 1.3 per cent of GDP, a sum that is in line with reasonable estimates for how much European governments must raise capital investment to meet 2030 emissions targets. And the sum is four times larger than the Conservative government’s current planned climate spending.

Neither party is planning to make big changes to the UK’s economic settlement with the EU, which means that one of the simpler methods of raising growth – rejoining the single market and customs union – is off the table. That makes it even more important to raise growth through domestic reform and investment. There is no point pretending that trade deals with far-off countries, deregulation or further tax cuts will do much to improve living standards. Britain’s pending accession to the trans-Pacific trade deal, a trade agreement between 11 Pacific rim countries, would raise output by 0.08 per cent, according to government modelling. Raising public investment will not be easy: the tax take will have to rise further to pay for it, at least for several years. Loading all of those tax rises onto workers, rather than the owners of capital and housing wealth, will only make it harder for the country to recover.

Neither party is planning to make big changes to the UK’s economic settlement with the EU, which means that rejoining the single market and customs union is off the table.

It may be politically difficult to raise taxes on older, wealthier people to fund investment that will benefit the young. But Brexit was imposed on working age people by older voters, who benefited most from rising house prices and EU membership. Such a strategy would not only be sensible – it would be fair, too.

John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform.