David Frost in bullish mood despite shortage of post-Brexit momentum

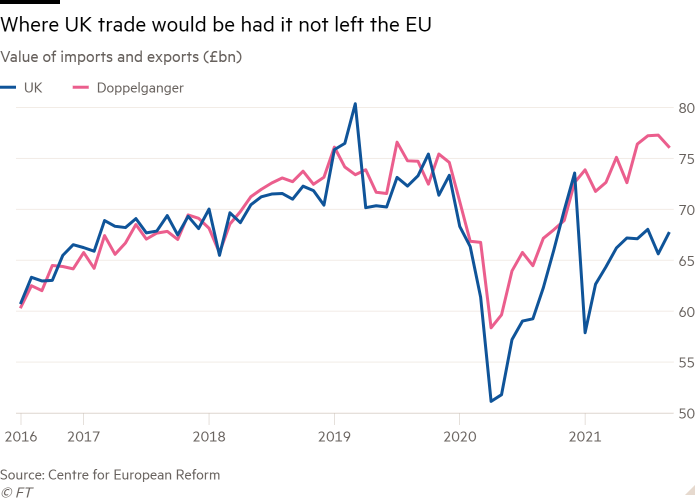

One way of trying to screen out the effects of Covid-19 and other factors is to measure UK trade against a ‘doppelgänger’ UK that had not exited the EU, built around modelling the trade performance of other advanced economies such as the US, Germany, Greece, New Zealand and Sweden. This is what has generated the below chart from John Springford at the Centre for European Reform (CER) whose work was referenced by the OBR in its October update.

Here he shares the latest iteration of the model for Britain after Brexit readers. It found that in September 2021, leaving the EU’s single market and customs union had reduced goods trade between the UK and the world by £8.5bn or 11.2 per cent.

Monthly trade data is quite volatile, but since May 2021 the model has shown a hit to UK trade of between 11 and 16 per cent, which is similar to pre-Brexit forecasts from the OBR and the Theresa May government.

Springford says that translating that ‘hit’ to trade into precise estimates of impact on GDP per capita (a key measure of living standards) is an imprecise science. The forecasts range from 2 to 9 per cent reduction in GDP compared to a UK that stayed in the EU.

Before the pandemic, the CER estimated that the effects of depreciation of sterling and foregone consumption and investment had reduced GDP by 1 to 3 per cent. Add the effect of reduced trade after a single market exit on top of that figure and, Springford says, there is “good reason to fear” that the OBR estimate of a 4-5 per cent smaller economy is “about right”.

Until now, these economic consequences have been largely met with a shrug by voters who were indeed relieved to have “got Brexit done” and then been consumed by dealing with the pandemic. It is also true that since no one lives in Springford’s “doppelgänger” UK most people don’t miss the economy they could, theoretically, have enjoyed.