Dutch elections: The end of the EU's pragmatic dealmaker?

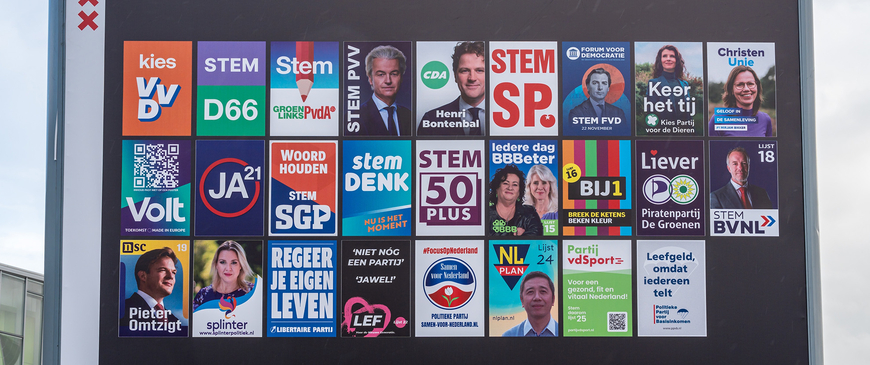

This week, the Netherlands heads to the polls. For the first time in 13 years, outgoing prime minister Mark Rutte is not on the ballot. Domestically, the election offers an opportunity to turn the page on an inheritance of intractable issues and scandals that hamstrung the last few governments headed by Rutte. For Europe, however, the changing of the guard may end the Netherlands’ recent role as an EU deal-broker. The Dutch electoral landscape is fragmented and volatile. Up to sixteen parties may end up in parliament. But while the Dutch might become a diminished force, it would be a mistake to completely write off their instinct for pragmatic dealmaking in Europe, especially if Franco-German relations continue to be poor.

The Netherlands as EU locomotive rather than brake

The election matters for the EU because the Netherlands is often a pivotal player. It is the biggest of the EU’s small economies and a large net contributor to the EU budget. The importance of the dynamic Dutch economy for the eurozone is growing. Germany’s economy has been stagnant for years, while the dynamic Dutch economy is now more than 6% larger than its pre-pandemic size. The country boasts Europe’s biggest port with Rotterdam and is home to its most important technology company, ASML, which has been at the heart of Washington’s efforts to cajole Europe into also throttling China’s access to semiconductors.

In the pre-pandemic era, the Netherlands leveraged such structural strengths to lead a coalition of small ‘frugal’ countries called the New Hanseatic League. The League vocally opposed further EU fiscal integration. But, especially after the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine, Rutte turned the country into more of a constructive bridge-builder. This included forging compromises between the Netherlands’ traditional ally, Germany, and Macron’s France.

Rutte’s last cabinet completed the transformation. Former UN diplomat Sigrid Kaag became finance minister, foregoing the brazen fiscal hawkishness of her predecessor Wopke Hoekstra that had irked member-states in southern Europe. Now, at the helm of the foreign office, Hoekstra took a more conciliatory stance. He, for example, joined a coalition of countries that called for a shift from unanimity to qualified-majority voting on EU foreign policy.

Rather than be the party of ‘no’, this government sought partners all over the Union. It pushed alongside member-states in central and eastern Europe for more advanced arms deliveries to Ukraine. The Dutch also toned down their traditional hostility to EU enlargement, instead emphasising the need for full compliance with rule-of-law and other milestones for the countries in the EU waiting room. And they even teamed up with Spain, a high-debt country, to lay the blueprint for the ongoing reform of the EU’s rules governing public debt and deficits. The Financial Times aptly summarised this new approach as “Dutch vow to be EU locomotive rather than brake”.

This newfound role for the Netherlands stabilised the EU at a time when the Franco-German relationship, which had previously powered Union initiatives, was fraying. Paris and Berlin have had repeated spats over energy and whether to buy weapons from the United States or produce them in Europe.

A national campaign about restoring trust in government

However, the Dutch government was divided and weak at home. The coalition was burdened by attempts to resolve a scandal in which tax officials wrongly accused thousands of parents of fraud based on ethnic profiling. Coalition partners continually argued over migration. And they were locked in an intractable stalemate with protesting farmers about how to reduce nitrogen emissions from intensive farming. The subsequent government collapse ended Rutte, Kaag and Hoekstra’s national political careers.

On the surface, the election campaign that ensued has lacked a core theme. European issues certainly barely featured. The overarching sentiment of the campaign seems to have been fatigue with, or even a repudiation of, the transactional, backroom-dealing style of power politics that marked Rutte’s years in charge. This may have served him to forge deals at the European level, but at the national level it increasingly fuelled scandals and resentment over a lack of accountability.

Instead, the parties in the campaign have ended up battling over ‘bestaanszekerheid’, which can be roughly translated as ‘livelihood security’. Strikingly, even the centre-right VVD campaigned on this terrain, which one would traditionally associate more with the left or centre-left. The cost-of-living crisis, along with most of the coalition’s disputes, can be subsumed under this banner. What has been on the ballot with ‘bestaanszekerheid’ is perhaps not so much a set of issues but repairing citizens’ trust in government itself.

Campaign dynamics

As a result, the turning points in the election campaign were driven less by substantive debates and more by changes in political personnel. The first was Rutte’s party’s choice of successor as leader of the centre-right VVD: justice and security minister Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius. She campaigned on tough migration limits and otherwise ran a media-savvy campaign in the spirit of Mark Rutte’s solutions-over-grand-visions mantra. A strong showing in opinion polls suggests she retained the loyalty of the VVD’s pro-business, low-tax base.

Another move that upended the race was the return of European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans to head up a newly created joint social democratic-green list. The joining of forces of Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA) and Groenlinks under Timmermans gave the alliance an enduring polling bump, although not enough to overtake the VVD.

The most profound upheaval was charismatic member of parliament Pieter Omtzigt entering the race with his own ‘New Social Contract’ (NSC) party. Omtzigt made his name by relentlessly holding the government to account in the childcare benefits scandal despite his then-party being in the government. He was then ruthlessly side-lined by Rutte and his own CDA leadership for a position in the last coalition negotiations in 2021. This contributed to him leaving the party and ultimately founding his own. But it also bolstered his image as a principled champion of the people. He has campaigned mainly on restoring the integrity of the state. Otherwise, he has portrayed himself as a centrist: conservative on immigration and climate change but leftist on reducing poverty and improving healthcare.

Finally, the anti-migrant, anti-EU, extreme right voter bloc seems to be travelling back to Geert Wilders’ PVV from his newer competitors on the far right.

Meanwhile, the surge in the BoerBurgerBeweging (BBB), a farmers’ party protesting the nitrogen reduction targets, has deflated.

The result has been a four-way race between the VVD, Groenlinks-PvdA, NSC and PVV for the top spot in a profoundly fragmented political landscape. The party that wins the most seats can traditionally lead coalition negotiations. Omtzigt has dithered on whether he wants to become prime minister. But even if the VVD wins, and Yeşilgöz becomes the first female Dutch prime minister, it will be hard to forge a majority without Omtzigt’s party. Timmermans faces the same constraint. So, the crux is whether Omtzigt will opt to govern over the centre, left or right. Omtzigt has kept his options open but sees a government over the right as ‘more realistic’.

Dutch orthodoxy and pragmatism on Europe are poised to return

The era of the Dutch being a constructive and agenda-setting dealmaker in the EU is probably weaker for now. A wave of senior party leaders with experience on the EU stage has retired from national politics. Rutte started his many years in office with occasional EU-sceptic notes. But the EU solidarity he felt in 2014 after the loss of many Dutch lives in the downing of the MH17 jet convinced him to solve more of his political problems by engaging the EU. It may take some time for his successor to draw the same lesson. Many of her possible coalition partners, like NSC and the BBB farmers party, are frequently critical of the EU. Omtzigt last weekend said that, while he does not agree with Viktor Orbán, the Dutch must take a much tougher stance in the EU like Hungary and Poland do. Wilders is outright hostile to the EU. As a result, any new government will probably be more hesitant to sign up to – let alone push – EU initiatives.

Certainly, on European economic policy, a return to Dutch orthodoxy is likely unless a coalition dominated by the left emerges. Both the VVD and Omtzigt’s NSC stress that they are opposed to giving the EU its own resources or taxation or further EU debt-issuance. With the VVD, NSC and PVV in the top-four parties, the Dutch tone on curbing migration will also harden in the EU arena. Dutch voters are generally sceptical of giving the EU more competences.

But while the Netherlands is less likely to actively shape the EU economic agenda, the country has frequently been more pragmatic than its rhetoric. This was true even in the era of the New Hanseatic League. Take the EU’s groundbreaking €800bn post-pandemic recovery fund, agreed to in 2020. After objecting vehemently to common European debt issuance, the Dutch signed up to the fund on the condition that it included an emergency brake for doling out cash to countries that do not fulfil certain conditions. That tool is now part of the EU’s most powerful weapon in the fight against democratic backsliding. Meanwhile, when it comes to sanctions on Russia, support for Ukraine, and European defence cooperation, the Dutch will continue to pull their weight. These initiatives still enjoy relatively widespread, albeit somewhat declining, support amongst citizens.

With their marriage in tatters, diplomats in Paris and Berlin should be watching the Netherlands’ election results with jitters. Will they no longer be able to call on a government in the Hague to mediate their conflicts and help forge European deals? A balkanised Dutch parliament will undoubtedly complicate matters. It provides another stark reminder to France and Germany to repair their relationship. But the Netherlands has always been governed by an amalgam of its political minorities able to hammer out coalitions, compromise and consensus. In the post-Rutte era, Dutch voters clamour for more transparent and principled governance at home. But that does not mean they want to completely forsake their country’s long-standing pragmatism internationally. So, with time, the Dutch might once again grease the wheels of European decision-making. But the odds are that in the period ahead the Hague’s tone vis-à-vis Brussels will harden. The brake may be back.

Sander Tordoir is senior economist at the Centre for European Reform. Sander works on eurozone monetary and fiscal policy, the institutional architecture of EMU, European integration as well as Germany’s role in the EU.